She’s Blonde, She’s Beautiful, and She Carries a GLOCK by Martha Thompson

by Martha Thompson, reblogging from Martha Thompson’s blog (2.19.15)

“She’s my ideal woman—blonde, beautiful, and carries a GLOCK.” I almost sprayed my just-sipped iced tea over the table. I was at a meeting with a man who wanted self-defense courses in his community, especially for college women.

I was reminded of that moment when I read the recent New York Times article “A Bid for Guns on Campuses to Deter Rape.”[1] Lawmakers in ten states—Florida, Indiana, Montana, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming –have introduced bills to allow guns on a campus to stop sexual assault. Sponsor of the Nevada bill, Assemblywoman Michele Fiore said: “If these young, hot little girls on campus have a firearm, I wonder how many men will want to assault them.” (Schwartz 2015).

For the moment, let’s set aside the blonde, beautiful, young, and hot remarks and focus on the argument that arming women is the way to stop sexual assault on campus. Jennifer Carlson (2014) says that confusing self-defense with gun defense limits women’s options, implies that “women must choose armed self-protection or no self-protection at all.”[2]

Imagine how different the conversation might be if instead of a focus on guns, it was on empowerment-based self-defense. What if the NY Times headline was: “A Bid for Empowerment-Based Self-Defense on Campuses to Deter Rape.” Imagine if being blonde, beautiful, young, and hot were not criteria for social protection or social vilification. What if the priority in legislation and news coverage was on empowerment-based self-defense programs built upon the idea that regardless of age, gender, disability, race, sexual orientation, and social class people have the right to bodily integrity and the right to make decisions about how their own bodies are treated.

[1] Alan Schwartz. 2015. “A Bid for Guns on Campuses to Deter Rape.” The New York Times.February 18. Retrieved February 19, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/19/us/in-bid-to-allow-guns-on-campus-weapons-are-linked-to-fighting-sexual-assault.html?ref=todayspaper

[2] Jennifer D. Carlson. 2014. “From Gun Politics to Self-Defense Politics: A Feminist Critique of the Great Gun Debate.” Violence Against Women 20 (3): 369-377.Violence Against Women 20 (3): 369-377.

Sneak Peek: Video about the Importance of Self-Defense

Coming soon to the SJFB blog! A 5-minute video explaining our latest academic analysis and why we must include self-defense training as part of our primary prevention efforts. Thanks to Dr. Beth Davison for filming and editing, and to the Barbies for starring in the video–here’s a short sneak peek!

Coming soon to the SJFB blog! A 5-minute video explaining our latest academic analysis and why we must include self-defense training as part of our primary prevention efforts. Thanks to Dr. Beth Davison for filming and editing, and to the Barbies for starring in the video–here’s a short sneak peek!

One in Three Men Admitting They Would Rape Will Not Be Solved by Consent Education Alone

On January 11, 2015, the news media reported on a new study by Dr. Sarah Edwards at the University of North Dakota and her colleagues that suggests almost 33% of college men admitted they would force a woman to have sex against her will if they thought they could get away with it; when the word “rape” was used, however, to describe the same behavior, about 13% of men admitted the same thing.

These data call into question the oft-touted claim that it is a small percentage of men who commit most of the rapes – or rather, who force women to have sex against their will; Dr. Edward’s data suggests this is not the case, if 13-33% of men are willing to do it.

This data is disturbing, but so is the recommendation that illogically follows, which is that what is needed is more and better consent education and teaching about healthy relationships. These recommendations are featured, even though these researchers report that admitting a willingness to force women to have non-consensual sex is not a function of confusion about consent or a misunderstanding of healthy relationships, but rather, is instead highly correlated with hostility toward women and hyper-masculinity: key components of rape culture.

Consent education will not make men believe that they should not rape women, whether or not they can get away with it, and understanding what constitutes a healthy relationship will not necessarily make men want it, particularly if their goal is to perform a version of masculinity which debases and devalues women as lesser, as other, as objects for the taking.

Self-defense training, in its enactment and practice of women’s bodies as powerful, as strong, as something other than inherently rapeable, is far more likely to change men’s and women’s concepts of gender and performance in sexual relationships. And more importantly, it significantly decreases the likelihood that men will “get away with it”; knowing that they could be seriously hurt if they try to force a woman to have sex against her will may make more men considering rape to pay close attention to conversations about consent.

‘Tis the season for setting the boundaries you want!

Remember the cootie catchers of our youth? They told us who we would marry. And – spoiler alert here – they don’t actually work. Despite the assertion of a cootie catcher one of the authors remembers fondly from 6th grade, she never did, in fact, marry Darrin Praeger.

The SJFB cootie catcher will not offer you the names of potential future partners, but will remind you of a number of techniques, both verbal and physical, that you can use in setting boundaries, both verbal and physical.

So have fun! So see below for our cootie catcher you can print, cut, fold, and give away! These make a great stocking stuffer or embellishment for your gift wrapped package. Remember, ‘tis the season for setting the boundaries you want!

Wishing you a safe, healthy and happy holiday season,

Martha McCaughey and Jill Cermele

SJFB Cootie Catcher Instructions:

- Print and cut round outside of cootie catcher

- Fold in half and in half again

- Open out, turn over so top is blank and fold each corner into the middle

- Turn over and repeat

- Turn over so you can see the pictures

- Slide your thumb and your finger behind 2 of the pictures and press together so they bend round and touch

- Turn over and repeat with the thumb and finger of the other hand for the other two pictures

- All the pictures should now be at the front with centres touching and you are ready to use your cootie catcher!

www.seejanefightback.wordpress.com

with thanks for the template to www.downloadablecootiecatchers.wordpress.com

Jane Gives Thanks

Readers, as we enter the holiday season, we at See Jane Fights Back would like to take a moment to express our appreciation.

We are grateful to our self-defense activist and scholar colleagues, for their efforts to empower women and girls, and in doing so, to shift the narratives about the perceived inevitability of sexual violence and the perceived omnipotence of perpetrators.

We are thankful for you, our readers, for reading and sharing our blog, and for all the feedback, comments, and stories you have shared with us.

Finally, we acknowledge all those who have been targeted for or experienced sexual violence; we admire and appreciate their courage and perseverance, their willingness to share their stories, and for reminding us all that resistance takes many, many forms.

PS. Snarky commentary returns next week.

Frequently Asked Questions about Self-Defense

With her permission, we give you Dr. Jocelyn Hollander’s FAQs about Self-Defense, with her terrific, well grounded answers to them.

Women’s Self-Defense Frequently Asked Questions* (*pdf file of this document is linked at the end!)

Jocelyn A. Hollander, Ph.D., University of Oregon September 15, 2014

What is women’s self-defense?

- Perhaps the most common stereotype of women’s self-defense is a woman – probably young, white, and fit – karate-kicking a stranger in a dark alley or parking garage. However, self-defense is far more than just physical fighting, and it is accessible to all women, regardless of their age, race, level of fitness, or physical ability. It also addresses far more than just assaults by strangers.

- There are many types of self-defense training. The kind that has been most frequently studied by researchers is empowerment self-defense. These classes:

- focus on the full range of violence against women, especially acquaintance assaults, which are the most common type of sexual assault.

- include awareness and verbal self-defense strategies as well as physical These skills empower women to stop assaults in their early stages, before they escalate to physical danger.

- teach effective physical tactics that build on the strengths of women’s bodies and require minutes or hours rather than years to master.

- offer a toolbox of strategies for avoiding and interrupting violence, and, rather than teaching a single “best” way to respond to violence, empower women to choose the options that are appropriate for their own situations.

- address the social conditions that facilitate sexual assault and the psychological barriers to self-defense that women face as a result of gender socialization.

Does self-defense prevent violence?

This is really two questions:

- First, can women’s resistance stop sexual assault? The answer is a resounding yes. There is a large and nearly unanimous body of research that demonstrates that women frequently resist violence, and that their resistance is often successful. This research, of course, includes many women without self-defense training.

- Second, does self-defense training decrease women’s risk of assault? There is a smaller but rapidly expanding research literature that suggests that women who learn self-defense are significantly less likely to experience assault. For example, Hollander’s research (2014) found that women who enrolled in a holistic, empowerment-based self- defense class were 2.5 times less likely to be assaulted over the following year, compared with similar women who did not take such a class. No women with self-defense training, but nearly 3% of women without training, reported being raped during the follow-up period.

Does self-defense increase a woman’s risk of injury?

- No. There is an association between resistance and injury, in that women who resist a sexual assault are also more likely to be injured. But research that looks at the sequence of events has found that in general, the injury precedes the resistance. In other words, women resist because they are being injured, rather than being injured because they resist. On average, resistance does not increase the risk of injury.

Shouldn’t we be putting all our resources into prevention strategies focused on perpetrators?

- No. Violence against women is a complex social problem. Ultimately, large-scale social changes will be needed before violence against women can be stopped. However, this kind of social change is slow – and so far, our efforts have not been very successful. If we focus only on perpetrator-focused, “primary” prevention strategies, we are condemning millions of women to suffering rape and sexual assault. While we wait for these efforts to work, empowerment-based self-defense training can provide an immediate, and effective, antidote for sexual violence.

- There has been little research on the effectiveness of prevention strategies focused on potential perpetrators. Most strategies that have been rigorously evaluated have been found to be ineffective at preventing violence.

- Preventing sexual violence will require a comprehensive range of efforts. Some efforts should be long-term (e.g., cultural climate assessment and change), others should be medium-term (e.g., bystander intervention training), and some should be short-term (e.g., self-defense training). We do not have to choose only one approach; a complex social problem requires that we address it on multiple fronts and in multiple ways.

Is self-defense training cost-effective?

- Yes. Sexual assault is very expensive, in terms of post-assault medical service, legal services, and human suffering. Self-defense training, in contrast, is quite inexpensive. A recent Nairobi-based study found that comprehensive self-‐defense training cost US$1.75 for every assault prevented, compared with an average of US$86 for post-assault hospital services. Given the higher cost of medical services, it is likely that the savings would be even greater in the United States.

Is self-defense victim blaming?

- No. Empowerment-based self-defense classes explicitly attribute responsibility for assault to perpetrators, not victims. Just because a woman is capable of defending herself does not mean that she is responsible for doing so.

- Although self-defense training is frequently lumped in with other kinds of risk reduction advice (e.g., staying out of public spaces, traveling with a buddy, wearing modest clothing, or avoiding alcohol), it differs in important ways. Staying home, relying on others for protection, and limiting one’s clothing or alcohol consumption all constrain women’s lives. Self-defense training, in contrast, expands women’s range of action, empowering them to make their own choices about where they go and what they do.

- Some people have worried that women who learn self-defense may blame themselves if they are later unable to prevent an attack. However, research has found that women with self-defense training who experience a subsequent assault blame themselves no more – or even less – than women without self-defense training. Moreover, women who are raped but physically resist are actually less likely than other women to blame themselves for their assault.

What else should I know about self-defense training?

- Learning self-defense empowers women in ways that go far beyond preventing assault. Self-defense training decreases women’s fear and anxiety and increases their confidence, their sense of self-efficacy, and their self-esteem. Learning self-defense helps women feel stronger and more confident in their bodies. Women report more comfortable interactions with strangers, acquaintances, and intimates, both in situations that seem dangerous and those that do not.

Further Resources and Research on Women’s Resistance and Self-Defense

What is women’s self-defense?

Thompson, Martha E. 2014. “Empowering Self-Defense Training.” Violence Against Women 20(3):351–359.

Does self-defense prevent violence?

Gidycz, Christine A, and Christina M. Dardis. 2014. “Feminist Self-‐Defense and Resistance Training for College Students A Critical Review and Recommendations for the Future.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 1524838014521026.

Hollander, Jocelyn A. 2014. “Does Self-‐Defense Training Prevent Sexual Violence Against Women?” Violence Against Women 20(3):252–269.

Orchowski, Lindsay M., Christine A Gidycz, and Holly Raffle. 2008. “Evaluation of a Sexual Assault Risk Reduction and Self-Defense Program: A Prospective Analysis of a Revised Protocol.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 32:204–218.

Sarnquist, Clea et al. 2014. “Rape Prevention Through Empowerment of Adolescent Girls.” Pediatrics peds.2013– 3414.

Senn, Charlene Y., Stephanie S. Gee, and Jennifer Thake. 2011. “Emancipatory Sexuality Education and Sexual Assault Resistance: Does the Former Enhance the Latter?” Psychology of Women Quarterly 35(1):72–91.

Sinclair, Jake et al. 2013. “A Self-‐Defense Program Reduces the Incidence of Sexual Assault in Kenyan Adolescent Girls.” Journal of Adolescent Health 53(3):374–380.

Tark, Jongyeon, and Gary Kleck. 2014. “Resisting Rape The Effects of Victim Self-‐Protection on Rape Completion and Injury.” Violence Against Women 20(3):270–292.

Ullman, Sarah E. 2007. “A 10-‐Year Update of ‘Review and Critique of Empirical Studies of Rape Avoidance’.”

Criminal Justice and Behavior 34(3):1–19.

Ullman, Sarah E. 1997. “Review and Critique of Empirical Studies of Rape Avoidance.” Criminal Justice and Behavior 24:177–204.

Brecklin, Leanne R., and Sarah E. Ullman. 2005. “Self-‐Defense or Assertiveness Training and Women’s Responses to Sexual Attacks.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 20(6):738–762.

Does self-defense increase a woman’s risk of injury?

Ullman, Sarah E., and R. A. Knight. 1992. “Fighting Back: Women’s Resistance to Rape.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 7:31–43.

Ullman, Sarah E, and Raymond A Knight. 1993. “THE EFFICACY OF WOMEN’S RESISTANCE STRATEGIES IN RAPE SITUATIONS.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 17(1):23–38.

Aren’t prevention strategies focused on perpetrators a better idea?

Gidycz, Christine A et al. n.d. “Concurrent administration of sexual assault prevention and risk reduction programming: Outcomes for women.” Violence Against Women. In press.

Gidycz, Christine A, and Christina M. Dardis. 2014. “Feminist Self-‐Defense and Resistance Training for College Students A Critical Review and Recommendations for the Future.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 1524838014521026.

Orchowski, Lindsay M, Christine A Gidycz, and M J Murphy. 2010. “Preventing campus-‐based sexual violence.” Pp. 415–447 in The Prevention of Sexual VIolence: A Practitioner’s Sourcebook, edited by K L Kaufman. Holyoke, MA: NEARI Press.

Breitenbecher, K. H., and M. Scarce. 1999. “A Longitudinal Evaluation of the Effectiveness of a Sexual Assault Education Program.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 14(5):459–478.

Hollander, Jocelyn A. 2014. “Does Self-‐Defense Training Prevent Sexual Violence Against Women?” Violence Against Women 20(3):252–269.

Sarnquist, Clea et al. 2014. “Rape Prevention Through Empowerment of Adolescent Girls.” Pediatrics peds.2013– 3414.

Sinclair, Jake et al. 2013. “A Self-‐Defense Program Reduces the Incidence of Sexual Assault in Kenyan Adolescent Girls.” Journal of Adolescent Health 53(3):374–380.

Is self-defense training cost-effective?

Sarnquist, Clea et al. 2014. “Rape Prevention Through Empowerment of Adolescent Girls.” Pediatrics peds.2013– 3414.

Is self-defense victim blaming?

Bart, Pauline B., and Patricia H. O’Brien. 1985. Stopping Rape: Successful Survival Strategies. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon.

Cermele, J. A. 2004. “Teaching Resistance to Teach Resistance: The Use of Self-‐Defense in Teaching Undergraduates about Gender Violence.” Feminist Teacher 15(1):1–15.

Gidycz, Christine A et al. n.d. “Concurrent administration of sexual assault prevention and risk reduction programming: Outcomes for women.” Violence Against Women. In press.

Orchowski, Lindsay M., Christine A Gidycz, and Holly Raffle. 2008. “Evaluation of a Sexual Assault Risk Reduction and Self-‐Defense Program: A Prospective Analysis of a Revised Protocol.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 32:204–218.

Rozee, Patricia D, and Mary P Koss. 2001. “Rape: A Century of Resistance.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 25(4):295–311.

What else should I know about self-defense training?

Brecklin, Leanne R. 2008. “Evaluation Outcomes of Self-‐Defense Training for Women: A Review.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 13:60–76.

Hollander, Jocelyn A. 2004. “‘I Can Take Care of Myself’: The Impact of Self-‐Defense Training on Women’s Lives.”

Violence Against Women 10(3):205–235.

McCaughey, Martha. 1997. Real Knockouts: The Physical Feminism of Women’s Self-Defense. New York: New York University Press.

Ozer, Elizabeth M., and Albert Bandura. 1990. “Mechanisms Governing Empowerment Effects: A Self-‐Efficacy Analysis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58(3):472–486.

Weitlauf, Julie C., D. Cervone, R. E. Smith, and P. M. Wright. 2001. “Assessing Generalization in Perceived Self-Efficacy: Multidomain and Global Assessments of the Effects of Self-Defense Training for Women.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 27(12):1683–1691.

Weitlauf, Julie C., Ronald E. Smith, and Daniel Cervone. 2000. “Generalization Effects of Coping Skills Training: Influence of Self-Defense Training on Women’s Efficacy Beliefs, Assertiveness, and Aggression.” Journal of Applied Psychology 85(4):625–633.

*A pdf file of the Self-Defense FAQs is here: SD FAQ

Color Names for the New Anti-Rape Nail Polish

Feminists wishing to indulge in the guilty pleasure of getting a manicure can soon do so while resisting rape at the same time. Some smart students at NC State–Ankesh Madan, Stephan Gray, Tasso Von Windheim, and Tyler Confrey-Maloney–created a nail polish that detects date rape drugs. The polish changes color if your polished fingernail is dipped into a drink that contains common date-rape drugs like Rohypnol, Xanax, or Gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid in it. Of course, we all know that the most common date-rape drug is plain old alcohol, but if a drug like this gets mixed into an alcoholic drink, its effect can magnify alcohol’s impact and lead to memory loss and even medical crisis.

The drug-detecting nail polishes are being developed under the name of “Undercover Colors” and have not been released to the public yet. Some protest the development and marketing of this nail polish based on the belief that the onus should not be on women to prevent and end rape and that the pretty polishes are victim-blaming. We agree in part: the onus should not be on women to end rape. But we believe that giving women more tools to protect themselves against rape is empowering, not victim-blaming. And while only a small percentage of perpetrators are drugging women’s drinks to facilitate their ability to rape, we are okay with women adding nail polish that can detect date rape drugs into our arsenal of resistance strategies. Not instead of changing the rape culture, or instead of holding perpetrators responsible for their behavior, or instead of teaching women active physical and verbal resistance strategies. In addition to those things.

The NC State students explained their purpose in developing the drug-detecting nail polish: “We hope this future product will be able to shift the fear from the victims to the perpetrators. . . .” We think this approach is actually quite radical, and it complements the advocacy of self-defense training. When women have strategies that shift the fear from themselves to the perpetrators, a fundamental feature of rape culture shifts: the pervasive fear felt most often by women.

Perhaps part of feminists’ skepticism about this anti-rape nail polish stems from the traditional point of polishing one’s fingernails and the accompanying bogus color names, such as “blushing bride,” “bikini so teeny,” “bouncer, it’s me!” “nein! nein! nein! OK fine”, “topless and barefoot”, and “damsel in a dress”. Ewww.

Since the anti-rape nail polish is still under development, we’d like to celebrate it as an additional device in women’s rape resistance toolkit, and in the spirit of feminism and wry humor, reclaim nail polish as a tool of the resistance by offering the following names for the Undercover Colors nail polish colors:

REDS

• Resistance red

• Red flag

• Fighting spirit

• Sign to Stop

PINKS

• You pinked the wrong night to plan a rape

• Boxing Barbie pink

• Pinko Commi Feminist

• Kiss off

YELLOWS

• Not today, Sun….

• Goodbye, not Yello(w)

• Gold Away

ORANGES

• Orange you sorry you tried this

• Orange will be your new Black

• Tread Gingerly

GREENS

• Green dot

• Preying mantis

• Yes means yes

• Leaves now

BLUES

• Blue balls

• Bluestocking

• Vicious streak

• You’re gonna sing the blues

BROWNS

• Mudd (that’s what your name will be)

• Taupe It Now

• Espresso NO

CLEAR

o Clear to me you’re a criminal

o Glass-ceiling smasher

o I see right through you

BLACKS

• Tough as Nails

• Black and blue from the Rolling Stones (and I don’t like it at all)

• Black the fuck off

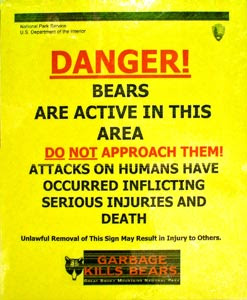

Bear Attacks and Man Attacks

On September 23, 2014 the Washington Post ran an article called “How to Best Survive a Bear Attack” just two days after Rutgers student Darsh Patel was tragically killed by a black bear when he and four friends were hiking in a New Jersey preserve.

Over the next two days, people commented on the Post website about how they’d have peed their pants, on how the group of young hikers should have stayed together as a group, on whether or not having food on them really mattered, and on whether or not black bears are really as dangerous to humans as the story made them out to be. Not one comment posted was upset at how the story, or the subsequent comments on the story, failed to mourn the tragic and violent death of Patel.

Not one comment posted accused the reporter or fellow commenters of victim-blaming. In fact, one even took the article’s how-to-avoid-this-fate message even further with this comment: “I love when city people write articles on what to do in a wild animal attack. How about staying in the aisles at Whole Foods instead if you don’t know what really goes on in the woods. What is sad is they (authorities) killed the bear who only did what is [sic] does in the real world of the forest.”

Imagine how people would react if within two days of a sexual assault we saw a news story with the headline, “How Best to Thwart a Sexual Assault.” Prediction: its author would be accused of victim-blaming, of not trying to get men to stop assaulting but instead of teaching women how to protect themselves from the assailants.  It’s true that, theoretically at least, the human male is far more capable of learning to abide by social rules than a bear is. Regardless, when a sexual assault is imminent, we would do well to ensure that women and girls have every opportunity to learn and employ strategies to ward off assailants—even while we work to find long-term solutions to the problem of sexual assault.

It’s true that, theoretically at least, the human male is far more capable of learning to abide by social rules than a bear is. Regardless, when a sexual assault is imminent, we would do well to ensure that women and girls have every opportunity to learn and employ strategies to ward off assailants—even while we work to find long-term solutions to the problem of sexual assault.  The Washington Post and others might defend the advice about how to defend yourself against a black bear on the grounds that we must prevent further tragedies and some knowledge can help us do that. They might also say that there is a surprising amount of research on bear attacks—from the differences between grizzly and black bears, bears around cubs versus bears who are alone, and even on whether or not being armed with a gun or bear spray is safer.

The Washington Post and others might defend the advice about how to defend yourself against a black bear on the grounds that we must prevent further tragedies and some knowledge can help us do that. They might also say that there is a surprising amount of research on bear attacks—from the differences between grizzly and black bears, bears around cubs versus bears who are alone, and even on whether or not being armed with a gun or bear spray is safer.

Exactly. And we have quite a bit of research on self-defense against the human male as well, and in particular the breed of party and acquaintance rapist found most often on college campuses. Why aren’t we sharing that research with young women in hopes of their warding off, thwarting, and surviving these men’s attacks? We have evidence-based, practical advice for women, but we don’t provide it for them because we fear it will be perceived as victim-blaming.  People seem to have no problem telling men and women how to fight off a black bear; nor do we. So let’s also not object to telling women how to fight off your average date, acquaintance, or party rapist. These assailants should be considered unarmed and dangerous, and, as with black bears, there are definite do’s and don’t’s that can be communicated.

People seem to have no problem telling men and women how to fight off a black bear; nor do we. So let’s also not object to telling women how to fight off your average date, acquaintance, or party rapist. These assailants should be considered unarmed and dangerous, and, as with black bears, there are definite do’s and don’t’s that can be communicated.  We aren’t going to tell women not to let a man smell food or to keep the dog on a leash (things commonly told to hikers who might encounter a bear). But let’s take the final piece of advice given in the Washington Post and substitute “sexual assailant” for “bear”:

We aren’t going to tell women not to let a man smell food or to keep the dog on a leash (things commonly told to hikers who might encounter a bear). But let’s take the final piece of advice given in the Washington Post and substitute “sexual assailant” for “bear”:

So what do you do if you come face-to-face with a black bear sexual assailant in the wild at a party??

Put up a good fight

Wave your arms, hold up your hands, try to appear as tall as possible. If you’re in a group, stand together. Clap, yell and throw things. “You’re trying to scare it away before it gets too close,” Stiver told ABC News. “Get a big stick, some rocks. Bang pots and pans.” If the bear sexual assailant doesn’t back off and — worst-case scenario — moves in for the attack, “do everything you can to get that animal off you,” Stiver said. Get physical. Punch and kick. “Give it a kick, start swatting the best you can. Stand up tall,” Forbes said. “These sorts of things have been shown to work quite well.”

We have no desire to mock the tragic death of the student in New Jersey, or anyone attacked by bears or people. But if it’s socially acceptable to offer strategies for thwarting a bear attack, we can damn well offer strategies for thwarting a sexual assault. We found some great bear warning signs that include how to stay safe and fight back if necessary. So we thought we’d create a few similar signs to advise campus co-eds about sexual assault.

Postscript: A word from one of our readers:

Dear Bloggers, I resent the fact that you created a warning sign with the phrase “Sexually Active Man Area” when, as only some active bears attack, only some sexually active men rape.

Yours,

Etc.

Recent Comments